“Every house in that neighborhood is 120+ years old. Our house is 127, I believe. It’s a 1,400-squart-foot Victorian with a great yard. And it’s historic from a foliage perspective too. We have great old trees.”

-Ricardo Baca, Lincoln Park neighbor

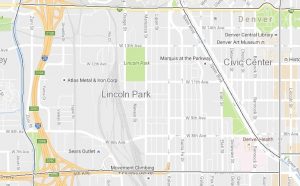

While Lincoln Park is one of Denver’s oldest neighborhoods, our informal man-on-the-street polling indicated that many Denver residents weren’t familiar with this neighborhood. Mention the Art District on Santa Fe however, and people could instantly picture the area. Other well-known landmarks in Lincoln Park include Denver Health, West High School, Sunken Gardens Park, Lincoln Park and Denver’s oldest restaurant, the Buckhorn Exchange. Read on to discover what brought the first residents to this spot along the banks of the Platte River and what current residents love about Lincoln Park.

A Brief History of the Lincoln Park Neighborhood

By Laura Ruttum Senturia

Library Director, Stephen H. Hart Library at History Colorado

The neighborhood of Lincoln Park has seen many changes over the course of its long history, which dates from the very beginning of Denver itself. Much of the architecture and history of the area has been overwritten multiple times, in some cases leaving nary a trace. Elements of the earlier years do remain, however, including one business that has witnessed most of the neighborhood’s history. Lincoln Park has hosted everything from farms to a military camp, railroads, residents, activists, and artists. Its history includes public housing projects and a cultural arts district to boot. Overall, the story of Lincoln Park is rich, although the inhabitants historically have been anything but.

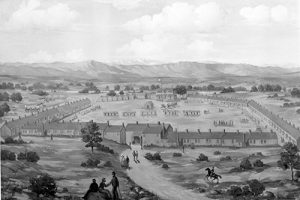

In 1861, Camp Weld was established in the area now known as Lincoln Park. Image courtesy Stephen H. Hart Library & Research Center, History Colorado.

Lincoln Park owes its earliest beginnings to its closest neighbor, Auraria. In November 1858, William G. Russell and a group of other southerners founded the town of Auraria on the southwest bank of the Cherry Creek, just across the creek from fledgling Denver City. The two towns grew in competition with each other until deciding upon the wiser solution of merging in April 1860. The neighborhood of Auraria quickly grew in both population and structures, but in the earliest years while it was still small was vulnerable to attack from the south (it was offered some protection by the Platte River to the west, and the rest of the city from the north and east). At the same time, the territory we think of as Colorado was scarcely populated, and a somewhat lawless part of largely unsettled Kansas Territory (soon to become Colorado Territory in 1861). Young Denver was in need of law and governance, and some felt a military camp would be just the thing to provide it.

Elsewhere in the U.S. at the same time, the Civil War was just beginning to brew. Colorado Territory was officially a part of the United States, however many of the southerners living in Denver had hopes of the territory joining the Confederacy. With all of these factors—from law and order, to preventing a Confederate land grab—it was clear to Territorial Governor William Gilpin that a military presence was crucial.

A snapshot of street life in early Denver in the Camp Weld area. Image courtesy Stephen H. Hart Library & Research Center, History Colorado.

In 1861, Gilpin orchestrated the building of Camp Weld, a few miles south of Auraria on the plains and agricultural region we know today as Lincoln Park. The military camp’s effect was mixed: the influx of rowdy soldiers into town served to decrease law and order by their public drunkenness and frequent quarrels. The camp served as a jumping-off point for troops from the 1st and 3rd Colorado regiments during the Battle of Glorieta Pass, which protected the greater southwest, including Colorado, from the Confederacy. Following the Sand Creek Massacre, however, the camp was abandoned in 1865. Almost no physical indications of the camp’s location or buildings remain. A house that included the original officers’ quarters—and that was the only remaining Camp Weld building—still existed at the northeastern corner of 8th and Vallejo as of the 1930s. Today, all that remains is one small stone historic marker right next to a warehouse (in the same spot where those officers’ quarters once stood) that indicates where the southwest corner of the busy camp had been.

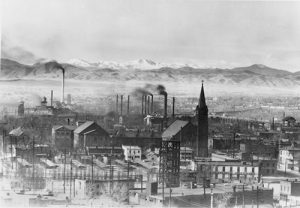

The next significant development for the area was the 1870s arrival of railroads in Denver. Railroad magnate William Jackson Palmer decided to run his Denver & Rio Grande Railroad through the Platte River Valley, between the Platte River and Cherry Creek, curving into downtown. This area, of course, includes the current Lincoln Park neighborhood. Railroads brought workers and factories (and the factories brought more workers!), all of whom settled in the area and called it home. As houses and other buildings went up, amenities such as schools, parks, shops, churches and the like soon followed. The park itself was built in 1885, and named in honor of President Lincoln. The neighborhood name soon followed.

The Buckhorn Exchange at 10th and Osage has served Denver diners for nearly 125 years. Image courtesy Stephen H. Hart Library & Research Center, History Colorado.

One of the businesses originally built to serve railroad and industrial workers is still opening their doors to Denverites nearly 125 years later. The Buckhorn Exchange restaurant is one of the many unique historic businesses that grace our city, and one of the few that still feature brass spittoons. Located right off the railroad tracks at 1000 Osage Street, the brick building has stood solidly in place since it was built in 1886. In 1893, the saloon was purchased by Indian scout and friend to Horace Tabor, Mr. Henry Zeitz. Zeitz opened shop as the “Rio Grande Exchange,” serving meals and liquor to Rio Grande Railroad workers. The saloon-turned-restaurant was run by three generations of the Zietz family, and was renamed the “Buckhorn” in the early 1900s. Henry Zietz is reported to have imported the saloon’s bar (originally located just inside the door, but now moved to the second floor) from his father’s hometown of Essen, Germany. Many of the more than 500 taxidermied animals on display throughout the building (which include a two-headed calf and several jackalopes) are reported to have been hunting trophies captured by Zietz and his son. During Prohibition, which in Colorado began earlier than elsewhere in 1916, the Zietz family converted the saloon into a grocery store. With the end of national Prohibition in 1933 they hurriedly converted back to a bar, and applied for a liquor license. Their alacrity paid off: the bar still operates under Colorado liquor license #1.

Considering the drastic changes to Denver and the Lincoln Park neighborhood in the past 124 years, it’s significant that the building, its interior contents, and the business have remained largely the same. Designated a national landmark in 1972, it will hopefully continue as a snapshot of an era for a long time to come.

Another long-standing Denver institution located in the Lincoln Park neighborhood is the Denver Health Hospital, previously known as Denver General. It would perhaps surprise many to know that the hospital’s history also goes back nearly to the beginning of our fair city, with the first medical provisions dating to 1860, and the first official building constructed in the hospital’s current location in 1873.

An undated photo of Denver General Hospital. Image courtesy Stephen H. Hart Library & Research Center, History Colorado.

With the raft of vaccinations, medical technology, and general sanitation we rely upon today, it is easy to forget that the health environment was significantly different in the 1860s and 1870s. Cholera, smallpox, typhoid, tuberculosis, measles and other highly dangerous diseases, in addition to high rates of malnutrition, were common threats feared by our recent ancestors. Occupational accidents at mines, smelters, on farms, and in railroad work were frequent. Women weren’t immune to ailments either, with high maternal and infant mortality rates common among all women, and high rates of violence and diseases like syphilis suffered by “working girls.” Finally, prior to an established rule of law and government in this newly formed city, death by disgruntled shotgun-bearing neighbor was not necessarily shocking.

Several attempts at establishing a city doctor preceded the hospital, but in 1870, Denver’s then home district of Arapahoe County appointed an official county physician in the person of Dr. John Elsner. Elsner initially struggled with outfitting a hospital, but convinced the county to assign $8,000 towards the cause, and the “County Hospital’s” first brick building was erected at 6th and Cherokee in 1873. The hospital has stood on this spot ever since. Additional buildings and wings followed, including an 1899 nurses’ training hospital; an 1892 quarantine hospital for highly contagious cases, and the hospital’s own power plant. In 1900, the complex got a mental health hospital—previously these patients had been kept in the basement—and a state-of-the art tuberculosis hospital was completed in 1921. The first automobile ambulance appeared in 1910, and for those interested in movement underground, in 1927 the complex built a series of tunnels linking many of the buildings.

A view of the early Denver skyline looking west, which includes the Eagle Flour Mills, Franktown Creamery and parts of Auraria and Lincoln Park. Image courtesy Stephen H. Hart Library & Research Center, History Colorado.

Renamed “Denver General” during the 1920s, the institution continued to be the official county-supported hospital. It first fell on hard times during the Great Depression of the 1930s, when money was scarce across the board. Patient admissions hit more than 17,000 annually by the middle years of the decade, in a system with only 400 beds. The hospital enhanced capacity through accepting Public Works Administration (PWA) funds during the Depression, and through serving as an Army hospital unit through WWII. Throughout the decades, public funds continued to provide a shot in the arm, but often years after they were first needed.

The hospital’s mission of serving the indigent and all Coloradans has meant it often bore the heavy weight of too many patients and too little funding. In the 1930s, the hospital saw nurses quitting under the stress of caring for 30-35 patients each shift, and in the 1970s-90s Denver General was known for the crush of violent crime victims it regularly treated. One oral history study of the hospital’s emergency room, published in 1989, drove home this point with the title “The Knife and Gun Club.”

The hospital was transferred away from direct management by the city to the Denver Health and Hospital Authority in the 1990s. To this day, the Denver Health Medical Center, as it is now known, continues in its mission as a “safety net” hospital that treats patients regardless of their ability to pay.

An undated photo of homes built during the Lincoln Park Housing Authority Housing Project. Image courtesy Stephen H. Hart Library & Research Center, History Colorado.

Yet another Lincoln Park institution that has a long history of serving the community are the North Lincoln Park Housing Projects. While these projects were known citywide for being rife with danger as recently as the early 1990s, it may surprise you to know they were actually on the national forefront of city services when they were built in the 1940s. Denver’s population suddenly skyrocketed with the U.S. entry into World War II, and, as current residents on the rental market know all too well, apartment scarcity means rents climb ever upwards. The decades of the 40s and 50s saw a housing crisis for the poor of Denver.

Fortunately for those who would come to call the neighborhood home, the city had built its first public housing development just prior to the war. The “North Lincoln Park Projects” were known nationally for being on the forefront of city planning in 1941, and, at 422 units, were one of the largest of their kind. These buildings located just south of Colfax between Osage and Mariposa offered affordable housing to a population that, in some cases, may otherwise have had few options. When the project first opened, a 6-room apartment rented for $18.75 a month. The project hosted residents for more than 50 years, and many of them fondly considered the community home.

As time passed, however, and Denver struggled through the lean years of the 1970s in particular, North Lincoln Park’s building stock became dilapidated and the overall area evolved into an overcrowded, drug-ridden place plagued by violent crime. By 1989, up to 1200 residents lived in the two block square area. In 1993, the housing authority began boarding up units in preparation for a 1994 complete demolition. The city planned 206 new homes (131 exist today) in a Victorian townhouse style, and the homes were designed to be subsidized, transitional housing for families, with half the number of residents the previous project saw at its peak. These much-needed newer developments were an improvement over what had gone before, while also representing 75 years of government-subsidized housing in the neighborhood.

A view of the first West Side High School located at 5th Ave. and Fox St. Image courtesy Stephen H. Hart Library & Research Center, History Colorado.

Another longstanding and beloved Lincoln Park institution is West High School (now hosting two different high schools in the same building). Started in 1880 as the “Central School” located at 12th and Kalamath, the Cowboys’s current home at 9th and Elati was built during the “City Beautiful” era, in 1926. Motorists who have passed the school while driving along Speer Boulevard will have noticed not only the school’s terra cotta tile Gothic architecture, but also the Sunken Gardens alongside the building. The gardens were intended to provide inspiring views for Denver’s residents, designed in imitation of the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair. Their park was both beautiful and functional, as it was engineered to absorb floodwater overflow from the Cherry Creek during the eras prior to its concrete containment. Further enhancing the gardens’s benefit to the community was the original a pavilion and pond that were popular in summer for swimming, and in winter for ice skating. The pond was removed in the 1950s, and replaced with a flower bed that continues to provide color and beauty for locals and commuters alike.

Much like the gardens outside its doors, West High School is more than just a pretty face. It also served as backdrop for one of Denver’s important, though less widely-known civil rights events. In March of 1969, 150 Chicano students at West High who were fed up with being on the receiving end of daily racism at school planned what was intended to be a peaceful walkout protest. The initial seed of the two-day event was disgust over a particular social studies teacher known for weaving inflammatory and disrespectful statements into his lectures. The protest was also inspired by experiences common for many Chicano students at the school, who felt that teachers institution-wide did not respect their culture or offer them the same opportunities provided to white classmates.

The former pavilion at the Sunken Gardens Park with West High School in the background. Image courtesy Stephen H. Hart Library & Research Center, History Colorado.

The students walked out of class on March 20, and were met on the school steps by Chicano rights activist and “Crusade for Justice” founder Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales. A large group of police officers arrived with tear gas and billy clubs shortly after the protest had begun, and the event turned into a melee of officers and students, pushing and punches. There were a number of injuries and arrests, and over the next several days the neighborhood experienced additional protests pitting people against police. After the dust settled only one arrested student was convicted, and Corky Gonzales was acquitted of all charges. More importantly, Chicano students at West now realized their power to advocate for change. They continued to press the Denver Public Schools system to increase teacher diversity and cultural sensitivity, and course offerings in Spanish as well as English. Just as importantly, their action contributed to the larger movement’s goal of demanding respect for Chicano culture.

The Art District on Santa Fe is the place to be for First Friday Art Walks each month. Image: Tara Bardeen

Turning from activism to business, no discussion of Lincoln Park would be complete without mentioning the jewel of the district, Santa Fe Drive. The street has historically hosted small mom-and-pop shops serving the daily needs of the community, anchored by two movie theaters: the Cameron Movie Theater at 7th (built in 1922), and the Santa Fe Movie Theater at 10th (built in 1927). Two movie theaters within 3 blocks of each other did not constitute a poor business plan back in the 1920s, when television had yet to begun siphoning off the audience. By the late 1950s, however, both theaters were in poor repair and the theater audience was much sparser. Both theaters spent significant numbers of years vacant, until the Cameron was purchased by Tony Garcia’s Su Teatro and converted to a stage theater performance space in the late 1990s. Su Teatro is a dual-language performance group—Spanish and English—that espouses social activism through theater. The group predominantly performs pieces written by Latinx (Latino/Latina) playwrights speaking to the life experiences of those in the community.

The Santa Fe theater had a different rebirth, reopening as the Aztlan theater in the late 70s, serving as a bar and music venue through the 80s, and then hosting infrequent private events until recently. There seem to be plans in the works to reopen the space as a music venue once again.

The Museo de las Americas educates the community about the diversity of Latino Americano art and culture from ancient to contemporary. Image: Tara Bardeen

Additional cultural anchors in the neighborhood include the Museo de las Americas at 9th, opened in 1994. The Museo is a community-focused museum that highlights “the diversity of Latino Americano art and culture from ancient to contemporary through innovative exhibitions and programs.” They are a collecting institution with a broad public programs schedule meant to be accessible to the surrounding community.

In addition to the museum, Santa Fe has become a magnet for art galleries and antique stores in recent years. Lincoln Park is conveniently placed within walking distance of downtown, and as the cultural perks of the neighborhood have grown, so too have the commercial ones. In the last handful of years Lincoln Park has gained a renovated recreation center in the park, as well as new restaurants, breweries, cafes, and even our collaborators on this project, the Knotty Tie Company (on 10th just off Santa Fe; they take walk-ins!)! Like many of Denver’s oldest neighborhoods, Lincoln Park has gone through multiple periods of growth and change, interspersed with periods of stagnation. It contains layers of history which are fascinating to unpeel and explore, and is one of the more recent beneficiaries (or victims, depending on your views of change) of Denver’s current development growth. From a military camp to an artists’ playground, Lincoln Park has seen almost everything else in between.

Wrap Lincoln Park Around Your Neck and Take It Everywhere

Get your own Lincoln Park-inspired bowtie, necktie or scarf here: Knotty Tie Co.

Save 20% on your order with code GOPLAYDENVER.

Interview with a Neighbor: Ricardo Baca (Near 10th & Lipan St.)

14 years.

What drew you to this neighborhood?

I went to school at Metro and so I’ve always loved it. The idea of living 5 blocks away from where I went to college was so fun, so I totally latched on to that. Also, its proximity to downtown, its proximity to the city, it’s just something that I’ve always known, that I wanted to be central. To me, that’s a big part of quality of life: walkability. When I worked at the Post, it was a 20-minute walk to work and now, it’s a 25-minute walk to work. I ride scooters; I ride bikes and I love that central downtown location and the ability to not have to start my car once a day, let alone once a week.

How would you describe the Lincoln Park neighborhood in 3-5 adjectives?

Latino, historic, alive.

How would you spend a perfect day in Lincoln Park?

The Molecule Effect serves coffee, tea, wine, beer, cocktails and food. Image courtesy The Molecule Effect

If the weather was good, probably walk the dogs, and we always walk them through the public housing kind of along Mariposa down through the entire park and down to 13th and then walk back up Kalamath or Lipan to the house. Grab coffee, a Bulletproof Coffee, at Molecule Effect (12th & Santa Fe Dr.). Nowadays they just have the cups chilled with a 1/4 stick of butter in there because that’s part of what makes it “bulletproof” and because it has gotten really popular. I’d probably walk up Santa Fe; drop the dogs off. And then go up to Grass Roots, a new hat shop on Santa Fe that has really cool hats like the flat-brimmed, kind of stoner lids; they’re a cool local company. I just bought a hat from them that’s in my pocket! So I’d probably go up there and see what’s going on there and say hello.

Maybe swing in the library and see what’s happening right there on 8th and Santa Fe. If was eating breakfast or an early lunch, it would be at El Taco (7th & Santa Fe Dr.). Then, maybe go back and read in the backyard. We’ve created a sanctuary in the backyard including our own mural and have invested in it by adding a fire pit and putting up a shade. It’s just kind of a happy place, so maybe read and have a drink in the yard and then if we’re feeling it, maybe going over to Interstate (10th & Santa Fe) for some whiskey. We have a bottle over there with our name on it; you let you buy a bottle for like $50 and then keep it there. So pop in for a nice sipper of Jameson from our own bottle and then walk down the street and maybe have one of the burritos at Chuey Fu’s. If we’re still feeling good, maybe just go up and just see what’s open on Santa Fe because we’re often surprised by what galleries are open on what nights. We kind of stumbled upon 3rd Friday Collectors Night on accident one night and now that’s one of our favorite things to do. It’s not the shit show that First Friday is and I love that shit show, and Third Friday is just kind of more chill and laid back and nuanced and you have more of an opportunity to get to know your neighbors and artists. So that would be a good day.

Some other cool places are:

Knotty Tie (10th between Santa Fe and Kalamath), and not because they’re part of this project, I was excited when they moved in because they really have made 10th Avenue a lot brighter.

Aztlan (10th & Santa Fe), I look forward to its future because it’s not being invested in now and it’s a little bit sad.

The Buntport Theater company writes all their own shows and they’re witty, clever, fun and hilarious. Image courtesy Buntport

My car is at Gary’s Auto Shop (12th & Santa Fe) right now, and I trust them, which is a lot to say of a mechanic.

Buntport (7th & Lipan) of course. We always end up at Buntport probably 4-5 times a year and that’s cool… I think they’re doing some of the most important artistic work in the city, without question.

I love Black Sky Pizza, or Black Sky Brewery (5th & Santa Fe). How random that there’s a Connecticut pizza with clams. The owners are apparently from the East Coast, so I ordered that pizza the first couple times I was there and was like, I see why this pizza is good. They also always have a unique independent cider on tap which is great because I don’t drink beer. So that’s always good.

I’m a fan of i Sushi (8th & Santa Fe) I think they do good work and I want them to be great, though they’re slightly inconsistent.

I buy tortillas right out of the factory, it’s just right on 11th. I think it’s called Tortillas Mexico (11th between Inca & Santa Fe) ; they’re in every grocery store. If you walk in the door, it’s like forklifts and giant bags of flour and masa and whatever else, but there’s a little office right there and you can just go up and buy tortillas for super cheap. They have their entire line right there. I think it used to be $1.25 a package, which is cheaper than at King Soopers and it’s fun to support a business in a direct way like that.

What might surprise people about your neighborhood?

I think Lincoln Park has surprised a lot of people in terms of the quality of life there. You know, unfortunately, Denver’s west side has a reputation for being a ghetto. And I think that’s undeserved and I don’t agree with it whatsoever. For example, when I first moved there, when I first bought my house, I had a family member try to talk me out of it. And granted, this is 14 years ago, but he had a history with the neighborhood, he had been with the DPD for a long time and he actually called me and said, “do not buy that house. I can’t tell you how many drug dealers I’ve arrested there and the murders and shootings.” But I didn’t care, I just knew; I believed in the neighborhood then and I believe in it now. I know it’s an amazing place to live and call home.

Also, they might be surprised by its rich latino heritage. I’m half Mexican and I’m really proud of that. I’ve found that there’s a kind of unique acceptance for not only being local, but also being of the heritage that that neighborhood it best known for.

What are some of the community hubs of your neighborhood?

I see neighbors at Molecule Effect and at Interstate regularly and at the Lincoln Park Lounge, at the park, at the 10th and Osage light rail station and that’s about it.

Where are your favorite places to walk?

It’s almost always through Lincoln Park, or Sunken Gardens; it’s always anchored by a park. Our reliance, especially in central Denver, on the parks system can’t be understated and that’s why it can be frustrating when you see parks like Wash Park and Cheesman looking so beautiful and vibrant and colorful, and you’ve got your neighborhood park, also managed by Denver Parks and Rec, and there’s dying grass and untended trash cans and clearly no supervision, whether there’s a minor tent city in the park or people not treating the park with respect. Our walks are always centered around the parks, those two parks.

We walk around the Art District, but not with the dogs. We’ll walk to dinner a couple times a month.

Live in Lincoln Park? We’d love to know what your perfect day would include!

More Historical Images of Denver General (Now Denver Health)

If you want to see even more, just head down to the Stephen H. Hart Library & Research Center at History Colorado (12th & Broadway). You don’t need an appointment to visit the library, just walk in. It’s free and the librarians are friendly and helpful! You can also check out some of their collection online: h-co.org/collections

- An automobile in front of the tuberculosis building at Denver General.

- The tuberculosis ward at Denver General

- Men shovel snow to clear the sidewalks outside Denver General after the Blizzard of 1913.

- Map of Denver from 1882.

Images: All images, unless otherwise noted, are courtesy Stephen H. Hart Library & Research Center, History Colorado.

Sources: “How the West Side Won: The History of West Denver,” by Phil Goldstein; “Denver General Hospital,” by Beverly Collins; “Denver: Mining Camp to Metropolis,” by Stephen Leonard and Tom Noel; “West Denver: The Story of an American High School,” by Gene Vervain; Zeitz Buckhorn Exchange, Office of Archaeology and Historic Preservation Site Form 5DV.700; DP, “West High, 1969,” March 2009: http://www.denverpost.com/2009/03/21/west-high-1969/; “Lincoln Park History blog,” https://lincolnparkhistory.wordpress.com/; Museo de las Americas website: http://museo.org/about-us/