The Highland neighborhood, also called Highlands, is bounded by Federal Blvd., 38th Ave., Inca St., the South Platte River and Speer Blvd.

“I think people forget how cool the river is, I mean the Platte. We see so much wildlife down there. For being in the heart of the city, we’ve seen bald eagles down there, coyotes, hawks, beavers, huge turtles, muskrats; pretty consistently you’ll see something. I think that people forget that that nature fix is right there, just a 10 minute walk from downtown.”

– Carl Reichley, Highlands neighbor

A Brief History of the Highland Neighborhood

By Laura Ruttum Senturia, Library Director at the Stephen H. Hart Library & Research Center, History Colorado

The real estate business has a famous saying about what makes a particular property valuable: “location, location, location.” Location has played a large role in the development of the Highlands neighborhood over the past one hundred and fifty years, as this Denver community has seen its fortunes ebb and flow, often based on its proximity to the Platte River and the neighborhood’s shifting edges.

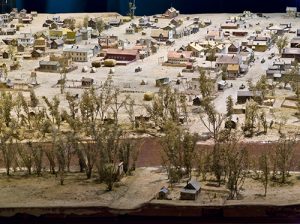

Detail of a diorama depicting Denver as it looked in 1860. This diorama, which was created as a WPA project, can be seen for free in the lobby of the History Colorado Center. Image courtesy Stephen H. Hart Library & Research Center, History Colorado

In 1858, William Larimer and David Collier platted a town on the high cliffs above where the South Platte and Cherry Creek converge, just across the river from the fledgling towns of Denver City and Auraria. They formed the Highland Town Company the following year. Larimer assumed that the area’s proximity to the water and both the Overland and Prospect Trails (today’s 15th and 38th Streets, respectively) would be helpful for trade. In actuality the river served more as a physical barrier isolating the Highland area from the business prospects of the rapidly growing twin cities below. The town of Highland never really took off as hoped, despite establishment of a ferry service across the Platte in 1859, and the first bridge, built in 1860. In April 1860, the separate town of Highland joined with Auraria and Denver City to form the new town of Denver, and the original Highland area became known simply as “North Denver.”

Despite the transportation challenges, over time people continued to settle in the area to the north and west of Denver, and in 1875, the City of Highlands incorporated just to the north of the original town site. What is now Platte Street served as one of the industrial and commercial districts for this city, with breweries, a power plant, and railroad-associated industries eventually taking hold. Initially, wealthy citizens were drawn to the residential parts of the neighborhood higher up the hill, prizing the Highlands for the views, artesian well water, and clean air up above the industrial pollution of Denver proper.

Portrait of General William Larimer painted in 1842. Image courtesy Stephen H. Hart Library & Research Center, History Colorado.

During this time period the southwest corner of current-day Highland was also laid out, built not organically but rather as a planned development. William A Bell and William Jackson Palmer planned this 288-acre plot they named “Highland Park,” intending for it to resemble a Scottish village. Many of the streets in the Highland Park section have retained their names, and so a glance at a modern map will show streets such as “Argyle,” “Dunkeld,” and “Caithness.”

Returning to earlier years, the town of Highlands had some fairly specific laws, including, from the 1889 list of ordinances, restrictions on hitching horses to trees (which were scarce and valuable, to be fair), riding horses “immoderately” (we assume they mean “no speeding!”), use of vulgar language, and kite flying. Any rowdies and ruffians with plans for profligate kite flying were surely sorely disappointed. The town also permitted liquor sales, but stipulated the cost of licenses at between $3000 and $5000 annually (at a time when that likely represented more than a decade’s worth of profits). Essentially, Highlands had the most annoying homeowners association, ever.

Much as the Five Points neighborhood saw during the same time period, when Capitol Hill became the trendy new ‘hood for the wealthy and well-connected in the 1890s, the Highlands also lost many of their rich citizens to the new district. This population loss, combined with the nationwide depression set off by the silver crash of 1893, further cemented things: the Highlands began to struggle economically. In 1896, threats from Denver’s mayor to cut bridge access between the two cities, paired with debt and a desire for better police and fire protection, led Highlands to join the list of esteemed neighboring cities Denver annexed and turned into official neighborhoods.

The “location factor” shaped Highlands’s industry as well: as Denver’s railroad and manufacturing industries grew along the east side of the Platte, Highlands was perfectly situated to serve these burgeoning business needs across the river. The neighborhood developed its first one-room schoolhouse in 1872 (later demolished by I-25), as well as banks, a firehouse, grocery stores, 13 churches, its own Town Hall (26th and Federal), a newspaper, bakeries, an amusement park (“River Front Park”), fairgrounds (the Sells-Floto winter quarters, meaning Buffalo Bill likely spent some time in the Highlands), and numerous other businesses.

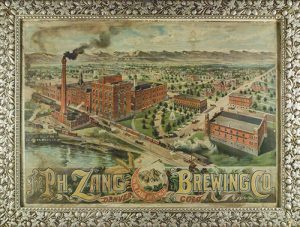

Chromolithograph in original frame showing the Zang Brewing Company in Denver c. 1890. Poster

also shows mountains in the background with Mount of the Holy cross in the center at bottom. Image courtesy Stephen H. Hart Library & Research Center, History Colorado.

Sitting on the banks of the Platte, with ready access to large amounts of water, the area also hosted a number of breweries up and down the river, the most famous of them being Philip Zang’s “Rocky Mountain Brewery,” later renamed for its owner. The breweries drew a number of German immigrants, with their longstanding cultural brewing tradition, who then settled to work in the area. Interestingly, just near the iron bridge built at 19th Street was a small Volga-German community (Germans from Russia, also called Volga Deutsch). The Zang Brewery itself was situated about where the Denver Aquarium is today, and further historical residue of the early residents can be seen in the “Brewmaster’s House” (also known as George Schmidt’s House), still standing at 2345 7th Street.

Germans and breweries were not the only example of industry bringing specific ethnic or national groups to the area: Highland also saw a number of Irish immigrants come after the 1870s, drawn by railroad work, of which many jobs were to be had on the Denver side of the river. As the Irish population grew there was great demand for Roman Catholic churches. This encouraged Bishop Machebeuf to oversee construction of St. Patrick’s in 1883. Not long after, due to both the strong Catholic presence, and the small-to-mid-scale agricultural opportunities in the area, Italian immigrants also began to settle in the Highlands in large numbers. Many Italians set up small truck farms to grow produce and flowers for sale. The efforts of these small-scale farmers were a large part of what made Denver the nation’s “carnation capitol” in the early 1900s, and also that established the Denargo agricultural market in current-day RiNo (now gone, but memorialized in the Denargo apartment complex). The Italian community’s growth created demand for a predominantly Italian church, and in 1894 the community’s needs were met by the organization of the Our Lady of Mount Carmel church at W. 36th and Navajo.

View of the Steps of Mount Carmel during Bidding for Statue, Procession for the Feast of Saint Rocco, c. 1940. This image is part of Italians of Colorado project. Image courtesy Stephen H. Hart Library & Research Center, History Colorado.

It was not long before the annexed Highlands, or North Denver, became known as a strong working class family neighborhood of predominantly Italian composition. The neighborhood had two Italian churches, an orphanage and school overseen by Mother Francis Xavier Cabrini, and four Italian language newspapers, in addition to the families and businesses. One may wonder, then, why Denver no longer has a Little Italy neighborhood, despite having such a solid Italian-American community history?

Part of the answer to that question comes with the aforementioned development of the I-25 corridor. After the end of WWII, Denver saw a significant population boom similar to today’s explosion of folks moving to the city. As the population grew, our built environment expanded, causing neighborhoods to both spread and infill empty areas. All of this growth during an era where most families could suddenly afford a car led to a lot of traffic, and created pressure for better means of moving both people and products from one end of our sprawling city to another. We also needed a way to link up with the newly developing Interstate Highway system.

Passengers stand around a J.G. Brill trolley coach (electric bus) at the corner of 16th and

Boulder Streets. The Olinger Mortuary can be seen nearby. Image courtesy Stephen H. Hart Library & Research Center, History Colorado.

Beginning in 1948, and continuing through to 1958, Denver addressed the north-south transportation need by building the 11.2 miles of the Denver Valley Highway, now more commonly known as I-25. In theory, the highway could have been built in several different spots at the edge of the city, but, similar to what happened to Globeville in the same era, the highway was routed right through the middle of the neighborhood. Where the eastern neighborhood border had previously been the Platte River, it was now essentially the highway, in practice, if not officially. Physical proximity to the railyards is one possible reason for this choice of location, but similar to Globeville’s situation it is also curious that a working class neighborhood of predominantly Italian immigrants—less likely to have “pull” in the halls of power—was the one slated for demolition. Fortunately for Highland only a small section was demolished, the separated segment (the Platte Street industrial district) is also small, and the highway essentially ran below the neighborhood, as opposed to right over it.

The section between the highway and the river, having lost residents over time and now physically separated, morphed into a grungy warehouse district, partially overshadowed by the 16th Street viaduct linking Highland to Denver. The industrial strip did continuously feature the bar we all know today as “My Brother’s Bar,” (15th and Platte), serving food and drinks to Highland residents and workers since 1970 under its current moniker, but also since its establishment as the “Highland House” in 1873. Through the 1940s and 1950s, the bar was a haunt of Jack Kerouac’s Denver buddy Neal Cassady, which should tell you all you need to know about the seedy character of the neighborhood during that era.

The lowest part of Highland struggled along with downtown Denver through the 1970s and 1980s. With the opening of the Paris on the Platte Café in 1986, the neighborhood served as a down-at-the-heels darling of many a melodramatic alternative teen, energized by the gritty abandoned feel of the place. As Denver’s fortunes lifted in the 1990s, so too did the fortunes of this part of the neighborhood, soon revitalized by REI, the Denver Aquarium, expensive shops and restaurants, and eventually, developers who put up apartments. Paris, sadly, was one of the casualties of the growth: it closed in January 2015.

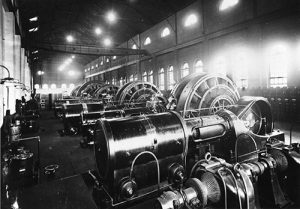

An interior view of the Denver Tramway Company power plant (now REI) at 14th and Platte. A line of large turbines fill the room and one wall is lined with electric switches. Image courtesy Stephen H. Hart Library & Research Center, History Colorado.

Looking at another favorite building along the Platte Street corridor is the large warehouse currently known as the national headquarters of REI, or Recreational Equipment Inc. At 90,000 square feet, with 3-story tall ceilings, the building is certainly perfect for a small climbing wall, kayak displays, and the like. The building has belonged to REI since 1998, but many Denverites may remember it from its previous incarnation as the Forney Transportation Museum. The Forney Museum, established in the building in 1969, was also a good fit for a space that could display numerous automobiles, trains, and other large vehicles. The Forney, however, was not the original tenant of the building. From its construction in 1901 until 1950, the large warehouse served as the primary power plant for the Denver Tramway Company. The building’s boilers and generators powered Denver’s extensive trolley system, which had switched to electric power at the beginning of the century. From powerhouse to museum to outdoor gear store, the building is an excellent example of adaptive reuse at its most creative and successful!

Turning to the “uphill” section of the Highlands, the neighborhood also experienced a typical trajectory from the 1940s to today. Highland went from containing predominantly Italian families, expanded to include Hispanic families (who built their own church—Our Lady of Guadalupe—in the 1940s), and, as the housing stock aged and the city experienced the recession of the 1970s, entered a period of shabbiness. In the 1980s, the Highlands began to see artists congregating in its small, affordable houses and commercial/cultural districts, and then in the 2000s saw an explosion of more well-to-do residents and high-end shops and restaurants. The “location, location, location” mantra could never be more true than it is today, with property costs in the area running in high digits, and construction cranes furiously tearing down small, former working family homes in order to build trendy condos.

An undated photo of George W. Olinger. Image courtesy Stephen H. Hart Library & Research Center, History Colorado

Smack dab in the middle of this growth is a modern Highlands feature with an interesting story: that of the restaurant Linger (30th and Umatilla). In a previous life Linger’s building housed the Olinger Mortuary, and the building still bears the original business’s giant rooftop sign. Indeed, the current clever restaurant owners have run with this theme in their name (just drop the “O”), marketing, and some of the serving ware.

Apart from the kitsch of the mortuary theme, however, many Denverites may not know much about the original business. The Olinger Mortuary was founded by John and Emma Olinger, who came to Denver in 1890, and was originally located at 15th and Platte. Their son George worked in and eventually inherited the family business. By 1900 George had turned Olinger’s into a chain of mortuaries, and by 1907 had added the Crown Hill Cemetery at West 29th and Wadsworth. Beyond serving Highlanders in their final moments, however, George was also known for his largesse to the community. He founded and for twelve years sponsored the “Highlander Boys,” a local alternative to the Boy Scouts. The club, founded in 1916, was meant to help neighborhood boys learn the skills and strengths they would need to be solid citizens. The program focused on the “mental, spiritual, social, and physical aspects” of a boy’s life, and included a competitive baseball team. During the early decades of the 20th Century the name Olinger was thus known for charitable reasons in the neighborhood, in addition to the perhaps morbid association we might have today.

The shift from a mortuary to a chic restaurant tells the 20th Century Highland tale quite well: since 1900 the area has gone from a working man’s neighborhood to a playground for Denver’s young elite. In fact, the “location, location, location” formula has been a factor from the very beginning: from a tiny town formed to take advantage of nearby trails and river, to a wealthy new neighborhood with amazing views of the rest of the city. As Denver’s population continues to grow at an astonishing pace, it will be interesting to see what Highland becomes next.

Wrap Highland Around Your Neck and Take It Everywhere

Find Highland-inspired bowties, neckties and scarves here: Knotty Tie Co.

Save 20% on your order with code GOPLAYDENVER.

Interview with Two Neighbors: Carl and Rachelle Reichley (3200 Block of Osage)

Carl: We’ve lived in lower Highlands for 7 years. I moved here from Park Hill thinking I’d scope out the neighborhood to see if I even liked it and haven’t left since because we love it.

What drew you to this neighborhood?

Rachelle: The house.

Carl: Yeah, the house is great. We’re right in the heart of some cool stuff; easy access to the freeway; and we can walk over to the Platte every morning. We used to walk our dog everyday; it was easy to get away from the hustle and bustle by walking over to the river.

Rachelle: I was living in Wash Park, and I loved it, I really loved it, but it feels more lively here. When we moved over here, Root Down had just opened, Lola was here, Little Man was here and Gallop Cafe, but so many of the places that are here now weren’t here then. And our house is loft style; so it’s got a real cool urban vibe…One of my favorite things is being able to walk everywhere. We can walk to Vitamin Cottage; we do bigger grocery runs, but in general, we’re a 3-person family and sometimes just two, so we don’t have to do that often. We can walk downtown and take classes. I like the walkability.

The stunning view from the Avanti rooftop. This food hall offers many different cuisines plus a full bar. Image: Tara Bardeen

Carl: We hardly ever drive. You can get to so many places just on foot. You don’t even need to ride a bike. We can get to Tattered Cover, Union Station, REI, hop on the Mall Ride, you can get to so many places so quickly. We went on a trip to San Fransisco and just pulled our luggage to Union Station to get on the train to go to the airport.

How would you describe the Highland neighborhood in 3-5 adjectives?

Carl: Is “hipster” an adjective? When we first moved in, it seemed like the neighborhood was on the verge of turning. Now there are Ubers clogging all the streets.

Rachelle: “Young” and “lively.” It’s maybe getting a bit too lively for us. There’s a lot of going out, a lot of bars and young professionals.

Carl: There are a lot of restaurants and a lot of breweries, so there are a lot of people. Perhaps the adjective “sterile” because there are a lot of stucco houses going in right now and older buildings being torn down. The neighborhood feels rather “transient,” like people move in and live here for a few years and then move out. It’s not like Park Hill where people move in and raise their family and stay for a long time.

Rachelle: It’s not grounded, it’s a very static-y neighborhood, with the “crackle and pop” of people moving in and out and construction.

Carl: But if you go farther north, you’ll still see grannies who have lived here for 90 years.

How would you spend a perfect day in the Highlands?

The exterior of Z Cuisine (temporarily closed) at 30th & Wyandot features a wheat paste photography gallery by artist Mark Sink. Image: Tara Bardeen

Carl: We would walk by the river for sure. We’d eat breakfast at home. We don’t eat out a lot even though there are so many restaurants over here.

Rachelle: I do feel like I have eaten more ice cream in the past five years since I moved here because we go to Little Man so often. So I’d say Little Man would definitely be a must.

Carl: We’d walk the loop (see their route below in Carl & Rachelle’s favorite places to walk response), go out for coffee at Carbon, which used to be Paris on the Platte. They do great coffee and great drinks there.

Rachelle: At first I didn’t want to like Carbon, because of the nostalgia of Paris on the Platte, but now it’s one of my favorite places to meet girlfriends for drinks; they have a great happy hour. I have actually gone there twice in one day, to get coffee and then later get drinks.

Carl: It’s a cool place, you can drink or not drink, caffeinate or not and the atmosphere is comfortable. If we went out for dinner, I would go to Z Cuisine, but unfortunately they’re closed right now. They had a great cassoulet.

Rachelle: When we went to Avanti for my birthday, it was really good. We’ve eaten over there quite a few times. So we might go there. I love Lola too.

Carl: You can’t beat Avanti’s views.

Rachelle: It really is lovely in there.

Little Man Ice Cream is a top destination for residents and visitors in the Highlands (2620 16th St). Image: Tara Bardeen

Carl: So, a perfect day would be walking, coffee at Carbon, a meal at Avanti, and ice cream at Little Man. The other day we got ice cream sandwiches there and they’re like “eyes roll up into your head” kind of good. We keep our radius pretty tight generally.

What might surprise people about your neighborhood?

Carl: I think people forget how cool the river is, I mean the Platte. We see so much wildlife down there. For being in the heart of the city, we’ve seen bald eagles down there, coyotes, hawks, beavers, huge turtles, muskrats; pretty consistently you’ll see something. I think that people forget that that nature fix is right there, just a 10 minute walk from downtown. You can see a Starbucks sign and at the same time see a beaver. If you go north along the river, things get very quiet.

Rachelle: Maybe the unusual juxtaposition you find here with the older residents, the new construction and young people coming into the neighborhood and the nature to be found by the river.

What are some of the community hubs of your neighborhood?

Rachelle: I would say Little Man is a huge hub in the community; they do so much within the community. It’s not just an ice cream place, there’s the pumpkin patch and the tree lot and there’s always something going on there.

Carl: And with their giveback program, that place is attractive way beyond just the ice cream and the architecture of a giant milk can.

The pedestrian bridge linking the Highlands with Platte St. and access to downtown. Image: Tara Bardeen

Rachelle: The farmer’s market in front of Lola was always a place I saw neighbors too.

Carl: The pedestrian bridge; we always see people we know crossing the bridge and Vitamin Cottage, of course.

Where are your favorite places to walk?

Rachelle: Down by the Platte. We start at 20th Street, and then cross over the viaduct and then go down into Cuernavaca Park, go by the Flour Mill Lofts and walk right along the river, then cross back at Commons Park and then come up the hill by Ale House and then back around to our house. We call it “walking the loop.”

Carl: Or sometimes down by the skateboard park; there’s a lot of variety.

Live in the Highlands? We’d love to know what your perfect day would include!

A Few More Photos From the Highlands

If you want to see even more, just head down to the Stephen H. Hart Library & Research Center at History Colorado (12th & Broadway). You don’t need an appointment to visit the library, just walk in. It’s free and the librarians are friendly and helpful! You can also check out some of their collection online: h-co.org/collections

- Ashland School at 29th Avenue and Firth Court in 1875.

- View of North Denver High School at 29th and Firth Court taken by photographer William Henry Jackson (1843-1942).

- View of the Steps of Mount Carmel during Bidding for Statue, Procession for the Feast of Saint Rocco, c. 1940. This image is part of Italians of Colorado project.

Images: All images, unless otherwise noted, are courtesy Stephen H. Hart Library & Research Center, History Colorado.

Sources: “1001 Colorado Place Names,” by Maxine Benson; National Register site file 5DV.541, Denver Tramway Powerhouse (REI – Recreational Equipment Inc); CDOT.gov website; “Italy in Colorado,” by Alisa Zahller; “Rediscovering Northwest Denver; It’s History, Its People, Its Landmarks,” by Ruth Eloise Wiberg; “Highland Neighborhood Plan,” Denver Planning & Community Development Office; “Compiled Ordinances of the Town of Highlands,” 1889; “From the Grave: A Roadside Guide to Colorado’s Cemeteries,” by Linda Wommack