“People actually live here. It’s not just someplace to drive through. There are things going on here and people living their lives here.”

-Antonia Montoya, Globeville neighbor

A neighborhood that once seemed far from downtown and far from people’s minds, Globeville is now front and center in a region-wide dialogue about how best to address the aging segments of I-70 that, along with I-25, divide the neighborhood. But what history lies buried underneath those six lanes of elevated highway? What originally brought residents to this part of town and what is it like to live in a place that most Denverites simply drive through on their way to somewhere else?

A Brief History of the Globeville Neighborhood

By Tara Bardeen

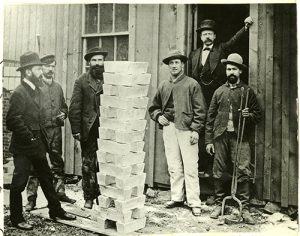

A group of men standing around a stack of silver bullion bars at the Argo Smelting Company in Black Hawk, Colo. circa 1873. A caption in the album indicates that this was the first silver made by Richard Pearce (b. 1838; Manager at Argo) and that Pearce “brought these men to Colorado with him from Swansea, Wales.” Image courtesy Stephen H. Hart Library & Research Center, History Colorado.

The story of Globeville really begins with the discovery of gold and silver in the mountains of Colorado in 1858 as this neighborhood sprang into existence to serve the needs of the mining industry and the railroads. As the decades passed, Globeville’s story has always been intertwined with the story of Colorado’s industries and modes of transportation of each era, as well as the story of the striving immigrant workers who came seeking the promise of prosperity and the opportunity to enjoy freedoms they had been denied in their home countries.

In the 1850s, as fortune seekers rushed to the Rockies to mine for precious metals, they quickly realized that they would need more than just shovels to extract riches from the complex ores that contained them. While many mine owners, scientists, entrepreneurs and charlatans proposed solutions; it was Nathaniel P. Hill, a chemistry professor from Brown University, whose method proved most successful. Hill opened the Boston and Colorado Smelter in Black Hawk, Colorado in 1867. The smelter processed ore from many mines in the area and became so popular that it outgrew its canyon location. In 1878, the plant moved to 6-acre plot of land north of Denver (roughly 44th to 47th from Fox Street to Pecos Street) near the South Platte River and the two railroad lines that served the region. The Boston and Colorado smelter employed 350 men of mostly of Welsh, Scottish, English, Irish and Swedish descent who lived next to the plant in a classic company town arrangement. This workers’ village was named Argo after the mythical ship in the story of Jason and the Argonauts. The smelter was eventually known by this name too.

The Holy Transfiguration Russian Orthodox

Church (47th & Logan) remains an icon of the Globeville neighborhood and continues to offer regular services 118 years after its founding. Image courtesy Stephen H. Hart Library & Research Center, History Colorado.

Not far from the Argo, Edward Holden founded the Holden Smelter in 1885, which was later purchased by Dennis Sheedy in 1889 and incorporated into the Globe Smelting and Refining Company. Sheedy also purchased land just south of the smelter to create a living quarters for the smelter’s workers. Originally named “Holdenville,” the small town was shortly thereafter changed to Globeville, after the largest employer in the area. Sheedy founded an additional living area across from the Globe Smelter and behind Washington Street known as “Sheedy Row,” which consisted of 10-24 small houses, a four-story hotel and the area’s only general store. As for Sheedy’s own residence, he elected to live in a mansion at 1115 Grant Street in the Capitol Hill neighborhood alongside other wealthy Denverites of the era.

By 1890, the Argo Smelter, Globe Smelting and Refining and the Omaha and Grant Smelter (located near today’s Denver Coliseum in the Elyria Swansea neighborhood) were the area’s largest industry, processing ore that arrived in railroad cars from as far away as Montana and Northern Mexico. While less than $35 million in gold and silver had been produced between 1858 and 1870, efficient ore processing and cheap rail transportation (along with the discovery of silver in Leadville and Aspen), resulted in more than $185 million in precious metals being processed from 1881 to 1890. By 1902, however, a diminishing supply of mineral-rich ore and changes in technology lead to the closure of the Argo Smelter.

The Holy Rosary Church at 4695 Pearl Street circa 1920-1930. Image courtesy Stephen H. Hart Library & Research Center, History Colorado.

The town of Globeville officially incorporated in 1891 with William H. Clark as its first mayor. For all intents and purposes, however, Dennis Sheedy is considered the founder of the city. Globeville’s city hall was located at 48th and Washington and the city jail could be found across the railroad tracks at Elgin and Washington. A few years later one of the area’s first churches, the German Congregational Church, opened at 44th and Lincoln in a small wooden building before a more permanent brick building was constructed for the church on that site in 1896 or 1897. Services were conducted in German and children attended “German School” at the church after their regular classes. These German-speaking residents of Globeville didn’t come from Germany, rather they were “Volga Deutsch” who had lived in villages along the Volga River in Russia, but left their homeland to pursue greater religious freedom in the United States.

Over the decades, more churches opened to serve the community of workers at the smelter and nearby railroads who were overwhelmingly of Eastern European descent including Volga Deutsch, Serbians, Croatians, Russians, Ukrainians, and Poles. In 1898 the Russo-Serbian Orthodox Church of the Transfiguration opened at 47th and Logan. Two years later, St Paul’s German Lutheran Church opened at 4438 Sherman and Garden Place Seventh Day Adventist Church opened at 4600 Logan. In 1902, St. Joseph Polish Catholic Church was built at 517 E. 46th Ave. and Father Jarzynski from Green Bay, Wisconsin, served as its first pastor. The Holy Rosary Church located at 47th and Pearl opened in 1919 to serve the area’s Slovenian Catholics. Many of these churches can still be found in the neighborhood today and most still offer regular services for the community.

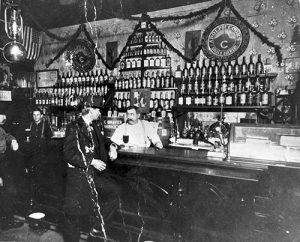

L. G. Reinhard’s Saloon circa 1901. Image courtesy Stephen H. Hart Library & Research Center, History Colorado.

By 1900, Globeville had a population of over 2,000 and had all the amenities of most Colorado towns of the time including hotels, boarding houses, dance halls, saloons, a school, a central park (Argo Park at 47th and Logan was dedicated in 1880), stores and even electric street lights on roughly every third block of the city. Most families in the area had small gardens and raised chickens, and perhaps a few pigs and a cow too. The sidewalks consisted of wooden boardwalks and the dirt roads through town were regularly watered down by the local government in order to keep down the dust. While life in Globeville was good, residents soon started to realize that becoming part of Denver could have some benefits including improved water access and street cars that could take residents right into downtown Denver.

In 1902, Globeville was annexed to Denver and as hoped, Denver water now came into the city and plans for a streetcar line down 45th Avenue and Washington Street were drawn up. The streetcar tracks were completed in 1908 and the #73 route took passengers north on Fox Street, then east on 45th Avenue to Broadway and then along Broadway to 52nd Ave. The #74 route ran north on Fox Street, then east on 45th before following Washington Street to 52nd Avenue. While the streetcar routes improved transportation in the area, it still took multiple steps to get to downtown Denver.

The smokestack of the Omaha and Grant Smelter is featured in the seal of the City and County of Denver just to the left of the capitol. The seal was designed by Denver artist Henry Read in 1901.

Globeville’s next growth spurt occurred in the 1920s when the types of industries operating in the area expanded from smelting and railroad work to include meat packing houses and rendering plants. As more women found work in the neighborhood at packing houses, garment shops and even as housemaids, more shops opened along 45th Avenue. While in earlier times, many families would board up their houses during the summer months to go work in the fields tending sugar beets, now most residents lived in Globeville year round. But Globevillelites as they were known, had already begun to feel like a lost neighborhood of Denver as they still lacked a direct route into downtown as well as many of the features they saw in other Denver neighborhoods including cement sidewalks, a sewer system and paved roads.

Construction of new infrastructure and facilities in the neighborhood were highlights of the 1930s and 1940s. The Globeville Road, which ran from 38th and Fox to 48th and Broadway was completed in 1930 and while it still wasn’t a direct route into Denver, it was an improvement in the area’s transportation options nonetheless. The year 1935 saw the completion of the Denver Sewage Plant, which was located east of Washington Street near the Globe Smelter. The Globeville Swimming Pool opened in 1940 and a baseball field was built in Argo Park in 1947. As the 1940s came to a close, Globeville’s residential areas were well filled in with predominantly single-story wood framed houses and 45th Avenue was lined with small businesses. Given the community feel in this working class neighborhood, residents were understandably upset when construction of Colorado’s Valley Highway (now known as I-25), which began in 1948, required neighbors to relocate and homes to be demolished.

The name “mousetrap” was coined by the long-time airborne radio traffic reporter Don Martin in the 1960s. Image: Google Maps

The 1950s started with a bang as the 352-foot smelter stack of the Grant Smelter (which had been the tallest chimney in the United States) was demolished using explosives on February 25, 1950. Residents recall the worst traffic jam the neighborhood had ever experienced as 3,000 – 4,000 people came to watch the demolition. This decade would see many more demolitions as buildings were removed to make way for the Stapleton Housing Project near the Globe Smelter in 1952, for the completion of I-25, and for the new I-70 highway that would run through the heart of the neighborhood along 46th Avenue. Residents rallied to fight the new highway and save the 31 homes slated for destruction. In fact, according to an article in the July 28, 1953 edition of the Denver Post, there was even talk of seceding from Denver. But despite their best efforts, the highway ploughed through. With the completion of I-25 in 1958 and then I-70 in 1964, the neighborhood had been literally divided into four largely isolated pockets.

As a result of the construction of the highways through the neighborhood, businesses and even some longtime Globeville families moved away to escape the noise, pollution and isolation. With close proximity to major transportation routes, Globeville saw increased industrialization and construction of distribution centers within the neighborhood. At this point, Denver city managers debated creating a full-fledged industrial park in Globeville in hopes of luring even more businesses to the area, but in the end all that made it to the books was a code prohibiting the modification or improvement of a “nonconforming structure in an industrial zone.” Unfortunately this meant that many residents, who happened to live in industrial zones due to the rather haphazard zoning of the area couldn’t even fix up a front porch without being in violation.

Ian’s Corner Tavern in Globeville, 1983. Image courtesy Stephen H. Hart Library & Research Center, History Colorado.

Resilient as always and welcoming of the new immigrants who settled in the neighborhood to work at nearby plants, Globeville survived a massive flood in 1965 and resisted decades of city attempts to turn the neighborhood an industrial zone or declare the neighborhood’s homes to be so rundown that the area could be cleared due to urban blight. The 1980s brought a deeper understanding of the lingering impact of smelting in the area as the soil and groundwater contamination was surveyed. Eventually, areas near the Argo Smelter and the Omaha and Grant Smelter were declared a Superfund site by the EPA. In the 1990s, Asarco, now owner of the former Globe Smelter, paid cleanup crews to move through the neighborhood digging up yards to remove and replace soil laced with heavy metals. Some twenty years later, the cleanup work is coming to an end; though pockets of contaminated soil remain under the railroad tracks and in areas of the neighborhood where soil could be “capped” instead of removed.

As the neighborhood’s history bears out, Globevillelites are hardworking, determined and dedicated to their community. For decades, residents have weathered the stresses of boom times and bust; the restructuring of their neighborhood by city mandates for new highways and changes in zoning; and the ever-present challenge of building community in an area known for its diversity of cultures, languages and religions. As Denver continues to experience rapid development that transforms neighborhoods, Globeville’s tight-knit, small town-esque, sense of community will again be tested, but perhaps this next chapter will also bring opportunities to mend broken connections and finally fulfill old promises.

Wrap Globeville Around Your Neck and Take It Everywhere

Find Globeville-inspired bowties, neckties and scarves here: Knotty Tie Co.

Save 20% on your order with code GOPLAYDENVER.

Interview with a Neighbor: Antonia Montoya (Near 45th & Grant)

Volunteers at the Birdseed Collective Food Program at the Globeville Rec Center. Antonia is second from the right. Image courtesy Birdseed Collective.

How long have you lived in Globeville?

27 years.

What drew you to this neighborhood?

I moved here to be close to family.

How would you describe the Globeville neighborhood in 3-5 adjectives?

Old, noisy and busy.

How would you spend a perfect day in Globeville?

It would probably be taking my grandson to the park (Argo Park, 47th & Logan). I go there I guess because it has just been there for so long. They have a good play ground. If I didn’t do that, I might take my grandson to see a movie, but it just depends on what’s going on.

I might also go to the panaderia on 45th and Pennsylvania. It’s all good there. The tortas and tacos are good.

What might surprise people about your neighborhood?

That people actually live here. It’s just not someplace you just drive through. There are things going on here and people living their lives here.

What are some of the community hubs of your neighborhood?

I guess it would have to be here (Globeville Recreation Center, 45th & Grant) because I don’t see anyone other than here. I’d like to get more people to come in here to get healthy foods. I’m here every Monday with the (Birdseed Collective) food program, so I see people then. I like getting to see people walk out with a nice big bag of groceries; with lots of healthy fruits and vegetables.

Argo Park has served as a community gathering place for more than 100 years. In earlier times, it had a pavilion, concessions, Sunday picnics and dancing. Today, it features an outdoor pool, baseball field, basketball court and playground. Image: Tara Bardeen

I’ve always been concerned about kids having enough to eat here when it was the (old) recreation center. At that time we ran the snack program and the tote program where the kids would go home with a bag of groceries every week. Now we do summer lunches and feed the kids free lunches in the park (Argo Park) during the summer. I see my neighbors there at the park too.

Where are your favorite places to walk?

I don’t do much walking around here. The area by the river is not a safe place; I wouldn’t recommend that anyone walk down there. I know that they would like it to be walkable down there, but we all know that stuff is going on down there.

Live in Globeville? We’d love to know what your perfect day would include!

A Look at Life at the Argo Smelter

If you want to see even more, just head down to the Stephen H. Hart Library & Research Center at History Colorado (12th & Broadway). You don’t need an appointment to visit the library, just walk in. It’s free and the librarians are friendly and helpful! You can also check out some of their collection online: h-co.org/collections

- Employees of the Argo Smelter Works in Denver, Colo. photographed by an unidentified photographer, circa April 24, 1902. The men are from left to right, J. D. Hale, H. V. Pearce., J. A. Anderson, F. Reynolds, Jr., C. [?] A. Montross, and J. F. Raynolds.

- A man at Argo Smelting Works in Denver, Colo. opening a slide in the bottom of a hopper to let the ore run into a furnace. This photograph was shot circa 1906-1907, possibly by Jesse D. Hale (1855-1946) who worked at the Argo Smelting Company for over twenty years and who compiled the photograph album.

- A man skimming the furnace of the north smelter directly into a granulating pit at the Argo Smelter Works in Denver, Colo. This photograph was shot in February 1906, possibly by Jesse D. Hale (1855-1946) who worked at the Argo Smelting Company for over twenty years and who compiled the photograph album.

- A man lifting an empty skimming pot hanging from an electric hoist at Argo Smelter Works in Denver, Colo. in March 1906. This photograph may have been shot by Jesse D. Hale (1855-1946) who worked at the Argo Smelting Company for over twenty years and who compiled the photograph album.

- Engineer Albert Moroney standing next to a generator in the Electric Power House of the Argo Smelter Works of Denver, Colo. This photograph was shot on Dec. 1, 1907, possibly by Jesse D. Hale (1855-1946) who worked at the Argo Smelting Company for over twenty years and who compiled the photograph album.

- Laborers at the Argo Smelter circa 1900 – 1910.

Images: All images, unless otherwise noted, are courtesy Stephen H. Hart Library & Research Center, History Colorado.

Sources: “Globeville: Part of Colorado’s History,” by Larry Betz; “Denver: Mining Camp to Metropolis” by Stephen J. Leonard and Thomas J. Noel; globevillestory.blogspot.com; Henrietta Hitchcock Manuscripts, MSS#1344 Colorado Historical Society; https://cumulis.epa.gov/supercpad/cursites/csitinfo.cfm?id=0801646; http://www.transfigcathedral.org