The Five Points neighborhood is bounded by Downing St., Park Avenue, 20th St., the Platte River and 38th St.

“Some of the greatest musicians and entertainers passed through here. I mean, they were walking up and down Welton Street. So it’s like, okay, Count Basie was here and I’m walking where he used to walk? It’s that connection to the past that I just really love.”

– Cha Ka, Five Points Community Advocate

Ball Park? Curtis Park? RiNo? That’s all Five Points. This neighborhood is home to some of Denver’s oldest homes and some of its newest developments. It’s a neighborhood that has always attracted creatives whether musicians during the Jazz era or artists who now make their studios along Larimer. Vibrant and dynamic, the past seems to be very much in dialogue with the present in Five Points and it is this layering of eras, cultures and stories that make this one of Denver’s most fascinating neighborhoods.

A Brief History of the Five Points Neighborhood

By Laura Ruttum Senturia

Library Director, Stephen H. Hart Library at History Colorado

The oldest residential neighborhood in Denver, Five Points has a fascinating and complex story that testifies to the long arc of history. The area has changed pretty significantly in demographics and economic structure over time, generally as a result of larger social developments in both Denver and nationally. People today think of the district as Denver’s “Harlem of the West,” a predominantly African American neighborhood known for its historic jazz clubs and nightlife. While this is true of the neighborhood for much of the Twentieth Century, it wasn’t how the area started out, and it appears to be experiencing change again today.

The 24th Street School (24th & Market) circa 1870-1890. Image courtesy Stephen H. Hart Library & Research Center, History Colorado.

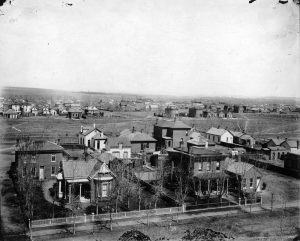

The oldest part of the neighborhood, Curtis Park, was founded as the first residential “suburb” of Denver, in the late 1860s. Built around a park donated by early Denver resident Samuel Curtis in 1868, the neighborhood housed the wealthy of the new city. Early denizens of the area included folks like Governor William Gilpin, and dry goods store owner J. Jay Joslin (long-time Denver residents, remember Joslin’s?). In 1871, the first streetcar line to the area was built, running along Larimer from 7th to 16th, then along Champa to 27th. The station serving Curtis Park was located at a funny five-point intersection of four streets: 26th avenue, 27th street, Welton Street, and Washington Street. Much like our bus and light rail systems today, in the 1870s the name of the final destination was printed on the front of each car to identify the particular route. How to list all four of those streets? Well, why not just describe the destination spot and call the station “Five Points?” The name stuck, much to the chagrin of the “society people” residents: the neighborhood shared a name with a notoriously violent slum in New York City.

A view of Stout Street and 29th. Image courtesy Stephen H. Hart Library & Research Center, History Colorado.

Nevertheless, most of the neighborhood was developed by the late 1880s, just barely in time for Capitol Hill to usurp Curtis Park/Five Points’s reputation in the 1890s. As Capitol Hill became the place to live for the well-heeled with deep pockets, Five Points settled into a slightly shabbier character. As railroads and industry grew northward alongside the western edge of the neighborhood (now RiNo), new working class jobs appeared, and some of the single-family homes in the area subdivided into rooming houses to accommodate workers. Many of these new industries, including railroads, factories, and agricultural produce markets like the Denargo Market, offered jobs to African Americans and Hispanics at a time when their upward mobility was otherwise constrained. As a result, Five Points began to diversify both ethnically and economically.

In the 1920s and 1930s, with the rise of the Ku Klux Klan in Denver, several forces limited not only the jobs available to African Americans, but also the neighborhoods where they could reside. Many Denver communities formed covenants requiring homeowners to agree they would not sell their house to people of color, and local real estate agents adopted an odious practice known as “redlining.”

Denargo Market at 29th and Broadway circa 1939. Image courtesy of Stephen H. Hart Library & Research Center, History Colorado

Redlining took its name from a practice begun in the 1930s, when the government generated maps that evaluated and “graded” neighborhoods based on various socio-economic factors, largely for insurance purposes. In practice, however, these maps were used by banks and real estate agents to discriminate against blacks and others. Real estate agents informally agreed industry-wide not to show homes beyond the red lines to African Americans, preserving those areas for whites only. Five Points, on the downgraded side of a red line drawn between Race and High Streets, had older housing stock in need of repair, and the proximity to industry and railroad lines. The redliners designated the area as one of the few Denver neighborhoods where African Americans looking to buy a house, or even rent, were able to do so without harassment.

While African Americans had lived in Denver since nearly the beginning of the town’s creation, World War II brought new growth. A large number of black servicemen, many of them from the southern U.S., served through the war at Lowry Air Force Base. Many of these men chose to settle in Denver afterwards, in order to take advantage of the opportunities presented by a younger, growing city. Many of these men bought homes and established families, institutions, and businesses in Five Points.

The Phylis Wheatley Branch of the Y.W.C.A. (2460 Welton Street). Image courtesy Stephen H. Hart Library & Research Center, History Colorado.

While some of the African American population who settled in Five Points lived here partially due to lack of options elsewhere, many also chose to live in the area for its churches, culture, and supportive society. The Denver neighborhood was not a dangerous ghetto like its New York counterpart, but rather a close-knit, healthy community of upstanding citizens who built a world through their own hard work. In response to discrimination in jobs and public services (including being banned from schools, libraries, hospitals, restaurants, and other institutions in the early years of the century), Five Points residents supplied their own institutions, from medical care to entertainment. As illustration, the “1948-1949 East Denver Directory” a city directory and phone book serving the Five Points neighborhood, lists businesses including attorneys, stationary and penmanship professionals, confectioners, chemists, a children’s nursery, electricians, insurance salesmen, librarians, two neighborhood newspapers, psychoanalysts, restaurants, and many, many other professions.

The home of Dr. Justina Ford is now home to the Black American West Museum (31st & California). Image courtesy Tara Bardeen.

The people of the neighborhood essentially created a parallel society of institutions and businesses serving African Americans, and they did it from the ground up. It’s impossible to fully capture all of the influential individuals and institutions of a neighborhood in a short article, but among the many pillars of the community were Dr. Justina Ford, the first African American woman licensed as a doctor in Colorado (up through 1950!), who is credited with delivering more than 7,000 babies in her more than 50 years of service; and Reverend Wendell Liggins, pastor at the Zion Baptist Church from 1941 to 1991. Institutions of note include the aforementioned Zion Baptist Church, at 24th and Ogden since 1911, but originally founded in Denver in 1865, making it the oldest African American church in Colorado. The church was a force pushing for social change and equality, advocating for desegregated schools as early as the 1920s. A neighborhood institution of another kind was the Phyllis Wheatley YWCA at 25th and Welton, which opened in 1916 and provided swimming, sports, entertainment, and community events for youth and adults alike for nearly fifty years.

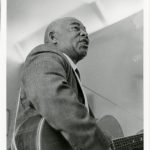

George Morrison, the bandleader responsible for the early growth of jazz in the neighborhood. Image courtesy Stephen H. Hart Library & Research Center, History Colorado.

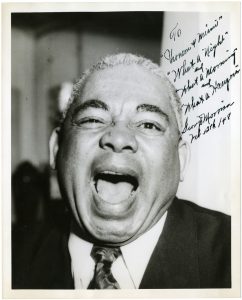

The cultural and musical fabric of Five Points brought visitors in from all over Denver, and in fact drew entertainers like Duke Ellington, Billie Holiday, and Charlie Parker from across the country to perform. In 1929, the Baxter Hotel at 27th and Welton changed hands, and opened as a hotel serving African American travelers (blocked from staying in many other, white-owned hotels). The new Rossonian Hotel and its adjacent jazz club would come to be one of the entertainment anchors of Five Points. Across the street Benny Hooper’s Ex-Service Men’s Club and Hotel, which had opened after World War I, also provided more music and dancing. A nightclub, however, is just a building: the musicians were what built the “Harlem of the West” brand. Particularly influential was classically trained musician and bandleader George Morrison, who brought early greats like Jimmie Lunceford to play Denver in the 1920s, formed his own local jazz bands, and eventually operated as a concert promoter for African American musicians across the city. Another influential Five Pointer, Leroy Smith, was a record store owner in the neighborhood who brought “race” records in from Chicago for sale in the 1940s. He, Morrison, Hooper, and others built an industry serving the whole city, in a neighborhood that had previously mostly served locals. For the many decades when racial segregation was part of life in Denver, Five Points was one of the few neighborhoods in town where people of all races mixed together in a social space.

An early Juneteenth celebration. Image courtesy Stephen H. Hart Library & Research, History Colorado.

Coming back around to the topic of segregation, the practice of it in Denver was overwhelmingly a negative factor in peoples’ lives, but it did result in the development and growth of Five Points as a unique place. As the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s began to succeed in pushing for equal access and protections for all Americans, practices like redlining and neighborhood covenants were challenged in the courts. The Fair Housing Act of 1968 deemed such practices illegal. One hundred years after the founding of the neighborhood, and still too slowly, social and institutional racism preventing outward movement to other neighborhoods lessened. Many Five Pointers, feeling crowded and disenchanted with the oldest existing housing stock in the city, chose to leave the neighborhood to buy newer homes in other areas. This loss of many successful citizens, combined with the national economic recession of the 1970s, depressed the neighborhood’s economy for several decades.

In the years since Five Points’s economy shrank, there have been various attempts to re-energize the area. One such example is the annual Juneteenth celebration. In 1991, the Five Points Business Association worked with both Mayor Peña and Governor Romer to decree June 13-16 the official celebration of the event in Denver. Juneteenth celebrates Texas slaves finally learning about emancipation in 1865, two and a half years after the fact, and serves as a larger celebration of African American culture and pride. The annual festival brings people from all over to Welton Street to celebrate.

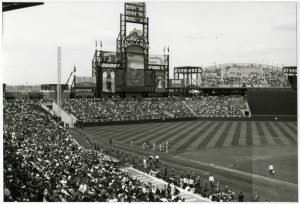

Additional developments that have improved Five Points’s economy have been largely fueled by Denver’s drastic population upswing since the late 1990s. Such growth generally equals economic development for a city, and indeed has for the larger Five Points district. Among the developments impacting Five Points have been the redevelopment of LoDo (formerly a sketchy warehouse district just south of the neighborhood), the building of the Coors Field Ballpark in 1991, the building of Denver Public Library’s Blair-Caldwell African American Research Library in 2003, and the reinterpretation of the former industrial region of RiNo (River North) as an artists’ district. New restaurants, bars, shops, residential buildings, and once again public transportation in the form of light rail have popped up with increasing speed. Five Points is currently in the midst of this swell, and many of the buildings that speak to the culture of the neighborhood, including most recently the Phyllis Wheatley YWCA, have been torn down to accommodate new growth. It remains to be seen how drastically the neighborhood’s culture and history will be impacted by development, but for Denver’s oldest neighborhood, it appears inevitable that change it will.

Wrap Five Points Around Your Neck and Take It Everywhere

“Five Points was once known as the ‘Harlem of the West’ because of its rich culture in Jazz music. Decades ago, famous Jazz musicians such Bille Holiday, Duke Ellington, Miles Davis, Nat King Cole, and others performed in bars and clubs throughout Five Points. This neighborhood has always been culturally diverse and the jazz music scene is still alive and well. My design serves to highlight this history of Jazz music, but also the diversity that is still so much a part of this neighborhood today.” – Laurel Gegner, designer at Knotty Tie

Get your own Five Points-inspired bowtie, necktie or scarf here: Knotty Tie Co.

Save 20% on your order with code GOPLAYDENVER.

Interview with a Neighbor: Cha Ka (Community Advocate)

Almost 11 years. I work and I play here. I love it and I love it that I’m here during this time of change. I’ve met some phenomenal people here.

My work with the community is about giving people information about affordable housing, development, finances, education and health. That’s what brings me here every day.

What drew you to this neighborhood?

The beautiful thing is you’ve got Cleo Parker Robinson Dance here, the Blair-Caldwell Library, Cervantes, the Roxy, which used to be a movie theater and night club, and the fact that this was the “Harlem of the West.” I love the pictures and the stories, both what I read and what I hear from the people who were born here. They say, “Oh you should have been here when this was happening or that was happening.” There are all these wonderful stories about Daddy Bruce who started the Thanksgiving dinner and it’s still going on. And the jazz! Some of the greatest musicians and entertainers passed through here. I mean, they were walking up and down Welton Street. So it’s like, okay, Count Basie was here and I’m walking where he used to walk? It’s that connection to the past that I just really love. And so you have all of these people like Madame C.J. Walker who used to sell beauty products and there are people who still live here who knew of her, whose parents or grandparents knew her. And then there’s the Rossonian and all the stories surrounding that. This is what makes this community special. There are still enough people around who know the stories.

When I first came here, this was one of the only neighborhoods that had a media center. We have newspapers, we have the public TV, the public radio. We have everything here in terms of the media. It’s great to have public TV down the street and all of these local publications too.

How would you describe the Five Points neighborhood in 3-5 adjectives?

Unique, vibrant, special.

How would you spend a perfect day in Five Points?

I’d have 15 meetings. Outside of the conferences and summits (organized by Cha Ka’s consultancy), we have roundtable discussions and one-on-one meetings. I like to support the local businesses, so I might have a meeting at Coffee at the Point (26th & Washington), at the Blair-Caldwell library (24th & Welton), at Randall’s at the New Climax (22nd & Welton), where they serve really good shrimp. Wherever people want to meet, then that’s where I want to meet.

For dinner would go to Dunbar (28th & Welton), the Welton Street Cafe (27th & Welton) or The New Climax. All of their food is good.

What might surprise people about this neighborhood?

How beautiful and safe it is. There’s so much propaganda about this being the crime neighborhood of Denver. We have as much crime as other neighborhoods, but the propaganda is “they kill people in Five Points.” Whenever I have meetings, I always invite people to come and see for themselves what it’s really like.

What are some of the community hubs in the neighborhood?

The Blair-Caldwell Library (24th & Welton) features a free museum exploring African American history in Denver on the second floor. Image courtesy Tara Bardeen

The Blair-Caldwell Library and coffee shops like Coffee at the Point. When there are special events that bring the community together, they’re often at The Climax.

I also think that there are businesses that anchor the community and are assets for the neighborhood like Crossroads Theater (26th & Washington), the 715 Club (26th & Washington), Zona’s pig ear stand (now closed), Courtesy Auto Service (26th & Clarkson), Stiger Barber Shop (aka Franklin Stiger Afro Styling, 28th & Welton), Kimball Hall (24th & Washington), Five Points Beauty & Barber (27th & Welton), Neat Stuff (25th & Welton), Brother Jeff’s Cultural Center (28th & Welton) and the two banks: US Bank and Wells Fargo.

What are your favorite places to walk?

I walk all over. We have our “Walk Welton” group on Saturday mornings at 8a and anybody can come and join us. We meet at Coffee a the Point and walk up to 35th and Downing and back to 23rd and then finish at the coffee shop. We walk Welton every Saturday morning just to walk Welton and to get people up and out of the house. It’s part of our health initiative to get people to be active and engaged. If I had 2 or 3 hours when I could just do that, I would walk all around. I’d walk over here and over there and see what’s happening. I’d go this way and that way. I’d just go up this block and down this one.

More Photos from Five Points Through the Years

If you want to see even more, just head down to the Stephen H. Hart Library & Research Center at History Colorado (12th & Broadway). You don’t need an appointment, just walk in. It’s free and the librarians are friendly and helpful! You can also check out some of their collection online: h-co.org/collections

- Engine Company 3 (2500 Washington) was organized in 1894 as Denver’s all-black firefighting team. It remained so until integration in 1958.

- George Morrison, the bandleader responsible for the early growth of jazz in the neighborhood

- A young girl at the YWCA.

- A produce vendor at Denargo Market circa 1939.

- Map of Denver from 1882.

Images: All images, unless otherwise noted, are courtesy Stephen H. Hart Library & Research Center, History Colorado.

Sources: “Pebbles on the Shore; Economic Opportunity in Denver’s Five Points Neighborhood, 1920-1950,” in Colorado History 2001, No. 5; “From Five Points to Struggle Hill: The Race Line and Segregation in Denver,” in Colorado Heritage, Autumn 2005; “Curtis Park: A Denver Neighborhood,” by William Allen West; “Curtis Park: Denver’s Oldest Neighborhood,” by William Allen West; “Walking Denver,” by Mindy Sink; “African Americans of Denver,” by Ronald Stephens, La Wanna Larson, and the Black American West Museum; “Curtis Park, Five Points, and Beyond: The Heart of Historic East Denver,” by Phil Goldstein; National Register of Historic Places Site Form and Nomination for Rossonian Hotel; “Denver Landmarks & Historic Districts,” by Thomas Noel; East Denver Business Directory, 1948-1949